Thursday, September 8, 2011

Monday, June 27, 2011

Picture Pages: Walker Evans

Monday, July 26, 2010

Downtown Birmingham

.jpg)

I love this building (and you can too - buy it!) It's called the "Leer Tower," but it's formerly the Thomas Jefferson Hotel. I just think it is gorgeous, even though it is in need of major renovation. It sits on 2nd Avenue North and 17th Street.

.jpg)

Ah, the Alabama Theatre. It's one of my favorite places in the world, and I can see it from my window. I always went as a kid to watch old movies during the summer movie season. It's really remarkable and just astonishingly beautiful. They also hold concerts there.

.jpg)

St. Paul's Catholic Church on 3rd Avenue North and 21st.

.jpg)

We went down the street to the Magic City Grille. It may not look fancy, but man can they cook. I am happy to be back in the land of good eatin'.

.jpg)

Here's Judge eating fried chicken, mashed potatoes, and green beans. Helpings are huge and it's cheaper if you go in the 22nd Street entrance rather than the 3rd Avenue North entrance.

.jpg)

Birmingham skyline at dawn from our loft window. You can see the Lyric Theater with its lights still on beneath the Wachovia tower.

.jpg)

The Lyric Theater. It's an old Vaudeville theater built in 1914. They're in the process of restoring it and you can find out more here. It's located on the corner of 3rd Avenue North and Eighteenth Street. We can see it from our window.

.jpg)

Last but not least, here is Pete's Famous Hot Dogs. It is on 2nd Avenue North and is an eighty year old (or so) establishment. It is so tiny! Getting a cold Coca Cola and a Special Dog on a hot summer day is pure perfection.

.jpg)

And here it is - the special dog!

Friday, June 25, 2010

Rock and Roll Wedding

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Folks: Photographer Series

Baron George Hoyningen-Huene (1900 - 1968) was a seminal fashion photographer of the 1920s and 1930s. He was born in Russia to Baltic German and American parents and spent his working life in France, England and the United States.[citation needed]

Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on September 4, 1900, Hoyningen-Huene was the only son of Baron Barthold Theodor Hermann (Theodorevitch) von Hoyningen-Huene (1859-1942), a Baltic nobleman, military officer and lord of Navesti manor (near Võhma), and his wife, Emily Anne "Nan" Lothrop (1860-1927), a daughter of George Van Ness Lothrop, an American minister to Russia. (The couple was married in Detroit, Michigan, in 1888.) He had two sisters. Helen (died 1976) became a fashion designer in France and the United States, using the name Helen de Huene. Elizabeth (1891-1973), also known as Betty, also became a fashion designer (using the name Mme. Yteb in the 1920s and 1930s) and married, first, Baron Wrangel, and, second, Lt. Col. Charles Norman Buzzard, a British Army officer.

During the Russian Revolution, the Hoyningen-Huenes fled to first London, and later Paris. By 1925 George had already worked his way up to chief of photography of the French Vogue. In 1931 he met Horst, the future photographer, who became his lover and frequent model[citation needed] and traveled to England with him that winter. While there, they visited photographer Cecil Beaton, who was working for the British edition of Vogue. In 1931, Horst began his association with Vogue, publishing his first photograph in the French edition of Vogue in November of that year.

In 1935 Hoyningen-Huene moved to New York City where he did most of his work for Harper's Bazaar. He published two art books on Greece and Egypt before relocating to Hollywood, where he earned his wedge by shooting glamorous portraits for the film industry.

Hoyningen-Huene worked before anything resembling contemporary flash photography was known.[neutrality is disputed] Working in huge studios and with whatever lighting worked best. There is something about the texture of his black and whites that one seldom finds in contemporary work. Beyond fashion, he was a master portraitist as well from Hollywood stars to other celebrities.[original research?]

He also worked in Hollywood in various capacities in the film industry, working closely with George Cukor, notably as special visual and color consultant for the 1954 Judy Garland movie A Star Is Born. He served a similar role for the 1957 film Les Girls, which starred Kay Kendall and Mitzi Gaynor, the Sophia Loren film Heller in Pink Tights and The Chapman Report.

In 1952 his cousin Baron Ernst Lyssardt von Hoyningen-Huene, whom he had adopted, married Nancy Oakes, the daughter of the gold mining tycoon Sir Harry Oakes. That union lasted until 1956 and produced one son Baron Alexander von Hoyningen-Huene. Baron Alexander von Hoyningen-Huene is also known as Sasha.

He died at 68 years of age in Los Angeles.

via Wikipedia, image via Glamour Splash

Folks: Photographer Series

Edward Henry Weston (March 24, 1886 – January 1, 1958) was an American photographer, and co-founder of Group f/64. Most of his work was done using an 8 by 10 inch view camera.

Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois on March 24, 1886. [1] He was given his first camera, a Kodak Bull's-Eye #2, for his 16th birthday, when he began taking photographs. His favorite hangouts were Chicago parks and a farm owned by his aunt. Weston met with quick success and the Chicago Art Institute exhibited his photographs a year later, in 1903. He attended the Illinois College of Photography.

In 1906, Weston moved to California, where he decided to stay and pursue a career in photography. He had four sons with his wife, Flora May Chandler (whom he married in 1909): Edward Chandler (Chan) (1910), Theodore Brett (1911), Laurence Neil (Neil)(1914) and Cole (1919). In 1910, Weston opened his first photographic studio in Tropico, California (now Glendale) and wrote articles about his unconventional methods of portraiture for several high-circulation magazines.

In 1922, Weston experienced a transition from pictorialism to straight photography, becoming "the pioneer of precise and sharp presentation". His pictures included the human figure as well as items of nature, including seaside wildlife, plants, and landscapes. Tina Modotti, his professional (and romantic) partner, often accompanied him to Mexico, creating much gossip in the media. Weston's sons were also frequent companions, receiving lessons in photography from their experienced father. Brett and Cole later embarked on their own careers in the field, along with Weston's grandson Kim and great-children, Christine and Jason.

After 1927, Weston worked mainly with nudes, still life — his shells and vegetable studies were especially important — and landscape subjects. Henrietta Shore was a companion in the 1930s; her paintings influenced him to photograph her shells.[2] After a few exhibitions of his works in New York, he co-founded Group f/64 in 1932 with Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke and others. The term f/64 referred to a very small aperture setting on a large format camera, which secured great depth of field, making a photograph appear evenly sharp from foreground to background. Weston also achieved great sharpness by not enlarging. He made contact prints from his 4x5" or 8x10" negatives. The detailed, straight photography that the group espoused was in opposition to the pictorialist soft-edged methods that were still in fashion at the time.

In 1937 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation awarded Weston a fellowship, the first given to a photographer. In 1939, he married his assistant, Charis Wilson, with whom he had lived since 1934. They divorced in 1945.[3] During this time he received exclusive commissions and published several books, some with Wilson, including an edition of Whitman's Leaves of Grass illustrated with his photographs. He also produced some of his few color photographs with Willard Van Dyke in 1947. Weston also collaborated on several volumes of his photographs with photography critic Nancy Newhall, beginning in 1946.

The Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson houses a full archive of Edward Weston's work.

Stricken with Parkinson's Disease, Weston made his last photographs at Point Lobos State Reserve in 1948. 1952 saw the publication of a 50th-anniversary portfolio of his work, printed by his son Brett. Brett and Cole Weston, as well as Brett's wife Dody Warren, were appointed to print 800 of what he considered his most important negatives under his supervision in the years 1955 to 1956.

Edward Weston died in his house on Wildcat Hill in Carmel Highlands in Big Sur, California on January 1, 1958, at age 71.

Folks: Photographer Series

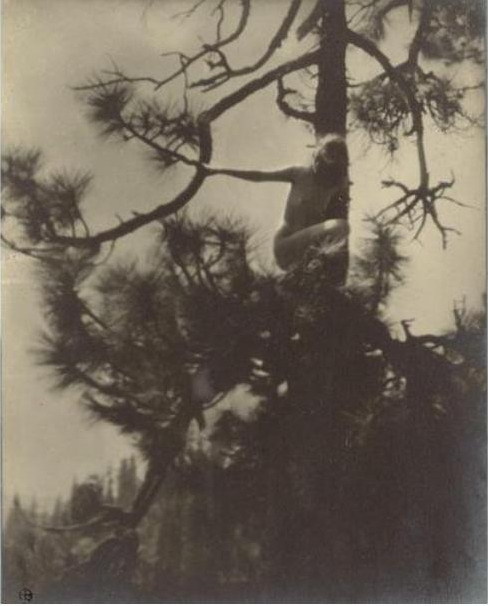

Anne Wardrope (Nott) Brigman (1869 - 1950) was an American photographer and one of the original members of the Photo-Secession movement in America. Her most famous images were taken between 1900 and 1920, and depict nude women in primordial, naturalistic contexts.

Brigman was born in the Nuuanu Valley above Honolulu, Hawaii on 3 December 1869. She was the oldest of eight children born to Mary Ellen Andrews Nott, whose parents has moved to Hawaii as missionaries in 1828. Her father, Samuel Nott, was from Gloucester, England. When she was sixteen her family moved to Los Gatos,California, and nothing is known about why they moved or what they did after arriving in California. In 1894 she married a sea captain, Martin Brigman. She accompanied her husband on several voyages to the South Seas, returning to Hawaii at least once.

Imogen Cunningham recounts a story supposedly told to her firsthand that on one of the voyages Brigman fell and injured herself so badly that one breast was removed.[1] Whether this is true or not, after 1900 she stopped traveling with her husband and became active in the growing bohemian community of the San Francisco Bay area. She was close friends with the writer Jack London and the poet and naturalist Charles Keeler. Perhaps seeking her own artistic outlet, she began photographing in 1901. Soon she was exhibiting in local photographic salons, and within two years she had developed a reputation as a master of pictorial photography. In late 1902 she came across a copy of Camera Work and was captivated by the images and the writings of Alfred Stieglitz. She wrote Stieglitz praising him for the journal, and Stieglitz in turn soon became captivated with Brigman's photography. In 1902 he listed her as an official member of the Photo-Secession, which, because of Stieglitz's notoriously high standards and because of her distance from the other members in New York, is a significant indicator of her artistic status. IN 1906 she was listed as a Fellow of the Photo-Secession, the only photographer west of the Mississippi to be so honored.[2]

From 1903 to 1908 Stieglitz exhibited Brigman's photos many times, and her photos were printed in three issues of Stieglitz's journal Camera Work. During this same period he often exhibited and corresponded under the name "Annie Brigman", but in 1911 she dropped the "i" and was known from then on as "Anne". Although she was well known for her artistic work, she did not do any commercial or portrait work like some of her comptemporaries. In 1910 she and her husband separated, and she moved into a house with her mother. By 1913 she was living alone "in a tiny cabin...with a red dog...and 12 tame birds".[1] She continued to exhibit for many years and was included in the landmark International Exhibition at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in New York in 1911 and the Internation Exhibition of Pictorial Photography in San Francisco in 1922.

In California, she became revered by West Coast photographers and her photography influenced many of her contemporaries. Here, she was also known as an actress in local plays [1], and as a poet performing both her own work and more popular pieces such as Enoch Arden [2]. An admirer of the work of George Wharton James, she photographed him on at least one occasion [3].

She continued photography through the 1940s, and her work evolved from a pure pictorial style to more of a straight photography approach, although she never really abandoned her original vision. Her later close-up photos of sandy beaches and vegetation are fascinating abstractions in black-and-white. In the mid-1930s she also began taking creative writing classes, and soon she was writing poetry. Encouraged by her writing instructor, she put together a book of her poems and photographs call Songs of a Pagan. She found a publisher for the book in 1941, but because of World War II the book was not printed until 1949, one year before she died. Brigman died on 8 February 1950 at her sister's home in El Monte, California.

Brigman's photographs frequently focused on the female nude, dramatically situated in natural landscapes or trees. Many of her photos were taken in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in carefully selected locations and featuring elaborately staged poses. Brigman often featured herself as the subject of her images. After shooting the photographs, she would extensively touch up the negatives with paints, pencil, or superimposition.

Brigman's deliberately counter-cultural images suggested bohemianism and female liberation. Her work challenged the establishment's cultural norms and defied convention, instead embracing pagan antiquity. The raw emotional intensity and barbaric strength of her photos contrasted with the carefully calculated and composed images of Stieglitz and other modern photographers.

via Wikipedia, image via Turn of the Century

Folks: Photographer Series

František Drtikol (3 March 1883, Příbram – 13 January 1961, Prague) was a Czech photographer of international renown. He is especially known for his characteristically epic photographs, often nudes and portraits.

From 1907 to 1910 he had his own studio, until 1935 he operated an important portrait photostudio in Prague on the fourth floor of one of Prague's remarkable buildings, a Baroque corner house at 9 Vodičkova, now demolished. Drtikol made many portraits of very important people and nudes which show development from pictorialism and symbolism to modern composite pictures of the nude body with geometric decorations and thrown shadows, where it is possible to find a number of parallels with the avant-garde works of the period. These are reminiscent of Cubism, and at the same time his nudes suggest the kind of movement that was characteristic of the futurism aesthetic.

He began using paper cut-outs in a period he called "photopurism". These photographs resembled silhouettes of the human form. Later he gave up photography and concentrated on painting. After the studio was sold Drtikol focused mainly on painting, Buddhist religious and philosophical systems. In the final stage of his photographic work Drtikol created compositions of little carved figures, with elongated shapes, symbolically expressing various themes from Buddhism. In the 1920s and 1930s, he received significant awards at international photo salons. Drtikol has published:

- "Le nus de Drtikol" (1929)

- Žena ve světle (Woman in the Light)

Folks: Photographer Series

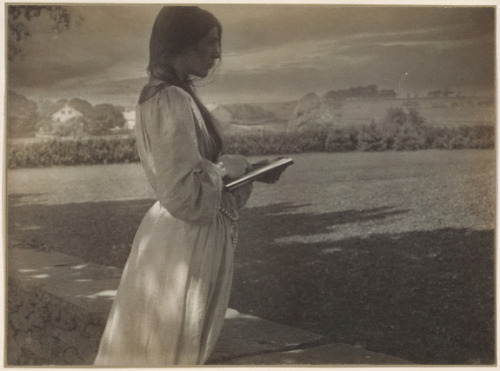

Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934) was one of the most influential American photographers of the early 20th century. She was known for her evocative images of motherhood, her powerful portraits of Native Americans and her promotion of photography as a career for women.

Käsebier was born Gertrude Stanton on 18 May 1852 in Fort Des Moines (now Des Moines, Iowa. Her father, John W. Stanton, transported a saw mill to Golden, Colorado at the start of the Pike's Peak Gold Rush of 1859, and he prospered from the building boom that followed. In 1860 eight-year-old Stanton traveled with her mother and younger brother to join her father in Colorado. That same year her father was elected the first mayor of Golden, which was then the capital of the Colorado Territory.[1]

After the sudden death of her father in 1864, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where her mother, Muncy Boone Stanton, opened a board house to support the family.[2] From 1866-70 Stanton lived in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania with her maternal grandmother and attended the Bethlehem Female Seminary (later called Moravian College). Little else is known about her early years.

On her twenty-second birthday, in 1874, she married twenty-eight year old Eduard Käsebier, a financially comfortable and socially well-placed businessman in Brooklyn.[1] The couple soon had three children, Frederick William (1875-?), Gertrude Elizabeth (1878-?) and Hermine Mathilde (1880-?). In 1884 they moved to a farm in New Durham, New Jersey, in order to provide a healthier place to raise their children.

Käsebier later wrote that she was miserable throughout most of her marriage. She said, "If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible…Nothing was ever good enough for him.”[1] At that time divorce was considered scandalous, and the two remained married while living separate lives after 1880. This unhappy situation would later serve as an inspiration for one of her most strikingly titled photographs – two constrained oxen, entitled Yoked and Muzzled – Marriage (c1915).

In spite of their differences, her husband supported her financially when she began to attend art school at the age of thirty-seven, a time when most women of her day were well-settled in their social positions. Käsebier never indicated what motivated her to study art, but she devoted herself to it wholeheartedly. Over the objections of her husband in 1889 she moved the family back to Brooklyn in order to attend the newly established Pratt Institute of Art and Design full-time. One of her teachers there was Arthur Wesley Dow, a highly influential artist and art educator. He would later help promote her career by writing about her work and by introducing her to other photographers and patrons.

While at Pratt Käsebier learned about the theories of Friedrich Fröbel, a 19th century scholar whose ideas about learning, play and education led to the development of the first kindergarten. His concepts about the importance of motherhood in child development greatly influenced Käsebier, and many of her later photographs would emphasize the bond between mother and child.[1]

She formally studied drawing and painting, but she quickly became obsessed with photography. Like many art students of that time, Käsebier decided to travel to Europe in order to further her education. She began 1894 by spending several weeks studying the chemistry of photography in Germany, where she was also able to leave her daughters with in-laws in Wiesbaden. She spent the rest of the year in France, studying with American painter Frank DuMond.[1]

In 1895 she returned to Brooklyn. In part because her husband was now quite ill and her family's finances were strained, she determined to become a professional photographer. A year later she became an assistant to Brooklyn portrait photographer Samuel H. Lifshey, where she learned how to run a studio and expand her knowledge of printing techniques. It is clear, however, that by this time she already had an extensive mastery of photography. Just one year later she exhibited 150 photographs, an enormous number for an individual artist at that time, at the Boston Camera Club. These same photos were shown in February 1897 at the Pratt Institute.[1]

The success of these shows led to another at the Photographic Society of Philadelphia in 1897. She also lectured on her work there and encouraged other women to take up photography as a career, saying, "I earnestly advise women of artistic tastes to train for the unworked field of modern photography. It seems to be especially adapted to them, and the few who have entered it are meeting a gratifying and profitable success."In the late 1890s Käsebier heard about a theatrical performance of cowboys, Indians and other American West characters called Buffalo Bill's Wild West". The show was performing in New York and had temporarily set up an "Indian village" in Brooklyn. Recalling her early days in Colorado, Käsebier went to the show and became enthralled with the faces of the Native Americans. She began taking portraits of them and soon became sympathetic to their plight. Over the next decade she would take dozens of photographs of the Indians in the show, some of which would become her most famous images.

Unlike her contemporary Edward Curtis, Käsebier focused more on the expression and individuality of the person than the costumes and customs. While Curtis is known to have added elements to his photographs to emphasize his personal vision, Käsebier did the opposite, sometimes removing genuine ceremonial articles from a sitter in order to concentrate on the face or stature of the person.[1]

In July 1899 Alfred Stieglitz published five of Käsebier's photographs in Camera Notes, declaring her “beyond dispute, the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day.”[3] Her rapid rise to fame was noted by photographer and critic Joseph Keiley, who wrote "a year ago Käsebier's name was practically unknown in the photographic world...Today that names stands first and unrivaled...".[4] That same year her print of "The Manger" sold for $100, the most ever paid for a photograph at that time.[5]

In 1900 Käsebier continued to gather accolades and professional praise. In the catalog for the Newark (Ohio) Photography Salon, she was called "the foremost professional photographer in the United States."[5] In recognition of her artistic accomplishments and her stature, later that year Käsebier was one of the first two women elected to Britain's Linked Ring (the other was British pictorialist Carine Cadby).

The next year Charles H. Caffin published his landmark book Photography as a Fine Art and devoted an entire chapter to the work of Käsebier ("Gertrude Käsebier and the Artistic Commercial Portrait").[6] Due to demand for her artistic opinions in Europe, Käsebier spent most of the year in Britain and France visiting with F. Holland Day and Edward Steichen.

In 1902 Stieglitz included Käsebier as a founding member of the Photo-Secession. The following year Stieglitz published six of her images in the first issue of Camera Work, along with highly complementary articles by Charles Caffin and Frances Benjamin Johnston.[7] In 1905 six more of her images were published in Camera Work, and the following year Stieglitz gave her an exhibition (along with Clarence H. White) at his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession.

The strain of balancing her professional life with her personal one began to take a toll on Käsebier about this time. The stress was exacerbated by her husband's decision to move to Oceanside, Long Island, which had the effect of distancing her from the New York's artistic center. To counter his action, she returned to Europe, where, through Steichen's connections, she was able to photograph the reclusive Auguste Rodin.

When Käsebier came back to New York, she found herself in an unexpected personality clash with Stieglitz. Käsebier's strong interests in the commercial side of photography, driven by her need to support her husband and family, were directly at odds with Stieglitz's idealistic and anti-materialistic nature. The more Käsebier enjoyed commercial success, the more Stieglitz felt she was a going against what he felt a true artist should emulate.[1] In May 1906 Käsebier joined the Professional Photographers of New York, a newly formed organization that Stieglitz saw as standing for everything he disliked – commercialism and selling photographs for money rather than love of the art. After this he began distancing himself from Käsebier, and their relationship never regained its previous status of mutual artistic admiration.

Eduard Käsebier died in 1910, finally leaving his wife free to pursue her interests as she saw fit. She continued to take a separate course from Stieglitz by helping to establish the Women's Professional Photographers Association of America. In turn, Stieglitz began to publicly speak against her work, although he still thought enough of her earlier images to include twenty-two of them in the landmark exhibition of pictorialists at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery later that year.

The next year Käsebier was shocked by a highly critical attack by her former admirer Joseph T. Keiley, published in Stieglitz's Camera Work. It's unknown why Keiley suddenly changed his opinion of her, but Käsebier suspected that Stieglitz had put him up to it.[1]

Part of Käsebier's alienation from Stieglitz was due to his stubborn resistance to the idea of gaining financial success from artistic photography. He often sold original prints by Käsebier and others at far less than their market value if he felt a buyer truly appreciated the art, and when he did sell prints he took many months to finally pay the photographer in question. After several years of protesting these practices, in 1912 Käsebier became the first member to resign from the Photo-Secession.

In 1916 Käsebier helped Clarence H. White found the group Pictorial Photographers of America[8], which was seen by Stieglitz as a direct challenge to his artistic leadership. By this time, Stieglitz's tactics had offended many of his former friends, including White and Robert Demachy, and a year later he was forced to disband the Photo-Secession.

During this time many young women starting out in photography sought out Käsebier, both for her photography artistry and inspiration as an independent woman. Among those who were inspired by Käsebier and who went on to have successful careers of their own were Clara Sipprell, Consuelo Kanaga and Laura Gilpin.

Throughout the late 1910s and most of the 1920s Käsebier continued to expand her portrait business, taking photos of many important people of the time including Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, Arthur B. Davies, Mabel Dodge and Stanford White. In 1924 her daughter Hermine Turner joined her in her portrait business.

In 1929 Käsebier gave up photography altogether and liquidated the contents of her studio. That same year she was given a major one-person exhibition at the Booklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Käsebier died on 12 October 1934 at the home of her daughter, Hermione Turner.

A major collection of her work is held by the University of Delaware.

via Wikipedia, image via Sloth Unleashed